3. Murderous Millinery

“From the trackless jungles of New Guinea, round the world both ways to the snow-capped peaks of the Andes, no unprotected bird is safe. The humming-birds of Brazil, the egrets of the world at large, the rare birds of paradise, the toucan, the eagle, the condor and the emu, all are being exterminated to swell the annual profits of the millinery trade. The case is far more serious than the world at large knows, or even suspects. But for the profits, the birds would be safe; and no unprotected wild species can long escape the hounds of Commerce. “ (W. T. Hornaday 1913) [1]

|

List Of Birds Now Being Exterminated For The London And Continental Feather Markets: |

|

|

Species. |

Locality. |

| American Egret | Venezuela, S. America, Mexico, etc. |

| Snowy Egret | Venezuela, S. America, Mexico, etc. |

| Scarlet Ibis | Tropical South America. |

| “Green” Ibis | Species not recognizable by its trade name. |

| Herons, generally | All unprotected regions. |

| Marabou Stork | Africa. |

| Pelicans, all species | All unprotected regions. |

| Bustard | Southern Asia, Africa. |

| Greater Bird of Paradise | New Guinea; Aru Islands. |

| Lesser Bird of Paradise | New Guinea. |

| Red Bird of Paradise | Islands of Waigiou and Batanta. |

| Twelve-Wired Bird of Paradise | New Guinea, Salwatti. |

| Black Bird of Paradise | Northern New Guinea. |

| Rifle Bird of Paradise | New Guinea generally. |

| Jobi Bird of Paradise | Island of Jobi. |

| King Bird of Paradise | New Guinea. |

| Magnificent Bird of Paradise | New Guinea. |

| Impeyan Pheasant | Nepal and India. |

| Tragopan Pheasant | Nepal and India. |

| Argus Pheasant | Malay Peninsula, Borneo. |

| Silver Pheasant | Burma and China. |

| Golden Pheasant | China. |

| Jungle Cock | East Indies and Burma. |

| Peacock | East Indies and India. |

| Condor | South America. |

| Vultures, generally | Where not protected. |

| Eagles, generally | All unprotected regions. |

| Hawks, generally | All unprotected regions. |

| Crowned Pigeon, two species | New Guinea. |

| “Choncas” | Locality unknown. |

| Pitta | East Indies. |

| Magpie | Europe. |

| Touracou, or Plantain-Eater | Africa. |

| Velvet Birds | Locality uncertain. |

| “Grives” | Locality uncertain. |

| Mannikin | South America. |

| Green Parrot (now protected) | India. |

| “Dominos” (Sooty Tern) | Tropical Coasts and Islands. |

| Garnet Tanager | South America. |

| Grebe | All unprotected regions. |

| Green Merle | Locality uncertain. |

| “Horphang” | Locality uncertain. |

| Rhea | South America.[Page 120] |

| “Sixplet” | Locality uncertain. |

| Starling | Europe. |

| Tetras | Locality not determined. |

| Emerald-Breasted Hummingbird | West Indies, Cent, and S. America. |

| Blue-Throated Hummingbird | West Indies, Cent, and S. America. |

| Amethyst Hummingbird | West Indies, Cent, and S. America. |

| Resplendent Trogon, several species | Central America. |

| Cock-of-the-Rock | South America. |

| Macaw | South America. |

| Toucan | South America. |

| Emu | Australia. |

| Sun-Bird | East Indies. |

| Owl | All unprotected regions. |

| Kingfisher | All unprotected regions. |

| Jabiru Stork | South America. |

| Albatross | All unprotected regions. |

| Tern, all species | All unprotected regions. |

| Gull, all species | All unprotected regions. |

Table: reproduced from Hornaday (1913) Our Vanishing Wildlife. http://www.gutenberg.org

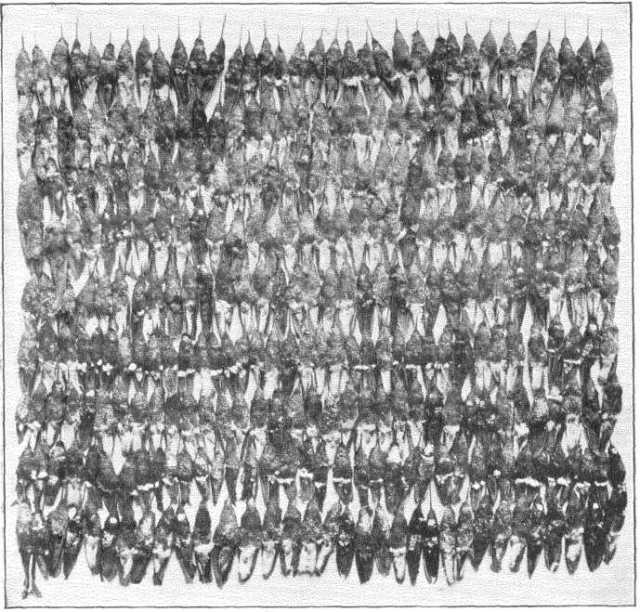

One catalogue from a Commercial sale room, covering the period between December 1864 and April 1885, included 404,464 West Indian and Brazilian birds of various descriptions, 356,389 East Indian birds, 6,828 Birds of Paradise, 4,974 Impeyan pheasants and 770 Argus pheasants. W. H. Hudson, a representative of the Society for the Protection of Birds (SPB,) recoiled with horror as he witnessed the sale of 80,000 parrot and 1,700 Bird of Paradise skins late in 1897:

“Spread out in Trafalgar Square they would have covered a large proportion of that space with a grass-green carpet, flecked with vivid purple, rose and scarlet”.[2]

At the height of “feather fashions” in the UK (around 1901-1910) 14, 362, 000 pounds of exotic feathers were imported into the United Kingdom at a total valuation of £19, 923, 000.[3] A single 1892 order of feathers by a London dealer (either a plumassier or a milliner) included 6,000 bird of paradise, 40,000 hummingbird and 360,000 various East Indian bird feathers. In 1902 an auction in London sold 1,608 30 ounce packages of heron (including the great heron and egret varieties) plumes. Each ounce of plume required the use of four herons, therefore each package used the plumes of 120 herons, for a grand total of 192, 960 herons killed.[4]

As time passed little seemed to change as this table compiled again by Hornaday in his 1913 publication Our Vanishing Wildlife underlines. The table details the number of feathers and skins being sold in the month of February at London’s busiest commercial sales rooms (Hale & Sons, Dalton & Young, Figgis & Co. and Lewis and Peat) in 1911

|

LONDON FEATHER SALE OF FEBRUARY, 1911 |

|||||

|

Sold by Hale & Sons |

Sold by Dalton & Young |

||||

| Aigrettes |

3,069 |

ounces | Aigrettes |

1,606 |

ounces |

| Herons |

960 |

“ | Herons |

250 |

“ |

| Birds of Paradise |

1,920 |

skins | Paradise |

4,330 |

bodies |

|

Sold by Figgis & Co. |

Sold by Lewis & Peat |

||||

| Aigrettes |

421 |

ounces | Aigrettes |

1,250 |

ounces |

| Herons |

103 |

“ | Paradise |

362 |

skins |

| Paradise |

414 |

skins | Eagles |

384 |

“ |

| Eagles |

2,600 |

“ | Trogons |

206 |

“ |

| Condors |

1,580 |

“ | Hummingbirds |

24,800 |

“ |

| Bustards |

2,400 |

“ | |||

|

LONDON FEATHER SALE OF MAY, 1911 |

|||||

|

Sold by Hale & Sons |

Sold by Dalton & Young |

||||

| Aigrettes |

1,390 |

ounces | Aigrettes |

2,921 |

ounces |

| Herons |

178 |

“ | Herons |

254 |

“ |

| Paradise |

1,686 |

skins | Paradise |

5,303 |

skins |

| Red Ibis |

868 |

“ | Golden Pheasants |

1,000 |

“ |

| Junglecocks |

1,550 |

“ | |||

| Parrots |

1,700 |

“ | |||

| Herons |

500 |

“ | |||

|

Sold by Figgis & Co. |

Sold by Lewis & Peat |

||||

| Aigrettes |

201 |

ounces | Aigrettes |

590 |

ounces |

| Herons |

248 |

“ | Herons |

190 |

“ |

| Paradise |

546 |

skins | Paradise |

60 |

skins |

| Falcons, Hawks |

1,500 |

“ | Trogons |

348 |

“ |

| Hummingbirds |

6,250 |

“ | |||

|

LONDON FEATHER SALE OF OCTOBER, 1911 |

|||||

|

Sold by Hale & Sons |

Sold by Dalton & Young |

||||

| Aigrettes |

1,020 |

ounces | Aigrettes |

5,879 |

ounces |

| Paradise |

2,209 |

skins | Heron |

1,608 |

“ |

| Hummingbirds |

10,040 |

“ | Paradise |

2,850 |

skins |

| Bustard |

28,000 |

quills | Condors |

1,500 |

“ |

| Eagles |

1,900 |

“ | |||

|

Sold by Figgis & Co. |

Sold by Lewis & Peat |

||||

| Aigrettes |

1,501 |

ounces | Aigrettes |

1,680 |

ounces |

| Herons |

140 |

“ | Herons |

400 |

“ |

| Paradise |

318 |

skins | Birds of Paradise |

700 |

skins |

Table: reproduced from Hornaday (1913) Our Vanishing Wildlife. http://www.gutenberg.org

The egret, supplier of the so-called ‘osprey’ feathers, were widely fashionable and therefore hugely in demand in both Europe and in North America from the 1890s onwards. The London feather trade required six egrets to yield one “ounce” of aigrette plumes. This being the case, the 21,528 ounces sold over a nine moth period, as above table states, translates as 129,168 egrets killed for the London plume markets alone.

On the quantity of egret and heron plumes offered and sold in London during the twelve months ending in April, 1912, Hornaday offer the following table:

| “OSPREY” FEATHERS (EGRET AND HERON PLUMES) SOLD IN LONDON DURING THE YEAR ENDING APRIL. 1912 | ||||

| Offered | Sold. | |||

| Venezuelan, long and medium | 11,617 | ounces | 7,072 | ounces |

| Venezuelan, mixed Heron | 4,043 | “ | 2,539 | “ |

| Brazilian | 3,335 | “ | 1,810 | “ |

| Chinese | 641 | “ | 576 | “ |

| ————– | ————– | |||

| 19,636 | ounces | 11,997 | ounces | |

| Birds of Paradise, plumes (2 plumes = 1 bird) | 29,385 | 24,579 | ||

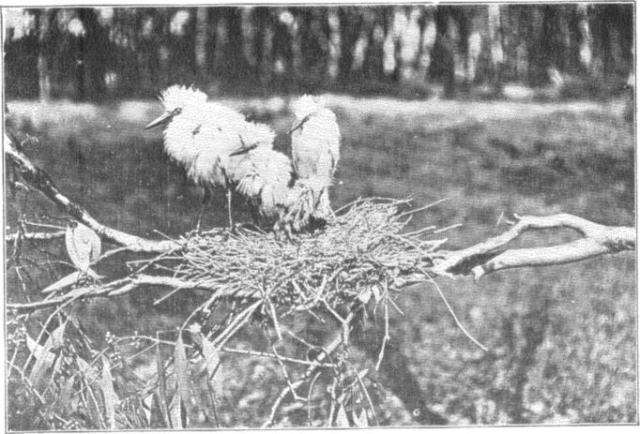

The overwhelming majority of egret plumes (at their finest during the breeding season) were obtained by shooting the birds as they nested, with the inevitable result that the young slowly starved to death.

NOWY EGRET, DEAD ON HER NEST Wounded in the Feeding-Grounds, and Came Home to Die. Photographed in a Florida Rookery Protected by the National Association of Audubon Societies. Photograph: Hornaday 1913.

By the turn of the century, this trade had nearly eliminated egrets in North America, and populations of numerous other bird species were also approaching extinction. Accumulating evidence was suggesting that plumage hunters were threatening the very existence of the emu in Australia, while the rhea, slaughtered at the rate of 3-500,000 annually was rarely to be seen on the Argentinian campo. Similarly trade in Huia feathers (a bird once native to New Zealand) increased to such an extent that the bird was declared extinct by 1907. Only taxidermy specimens of this once prized species remain.

Another casualty of the “plume boom” was the Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis). Considered a serious agricultural pest it was slaughtered in huge numbers by wrathful farmers. This killing, combined with forest destruction throughout the bird’s range, and hunting for its bright feathers to be used in the millinery trade, caused the Carolina Parakeet to begin declining in the 1800s. The bird was rarely reported outside Florida after 1860, and was considered extinct by the 1920s.

Millinery prepared dyed black skin, possibly of the now extinct Carolina parakeet in UACTC. Photo © Merle Patchett/UACTC

Close up of millinery prepared dyed black parakeet skin showing natural green colour – further evidence that this skin is that of the Carolina parakeet shot to extinction though the plume trade. Photo © Merle Patchett/UACTC

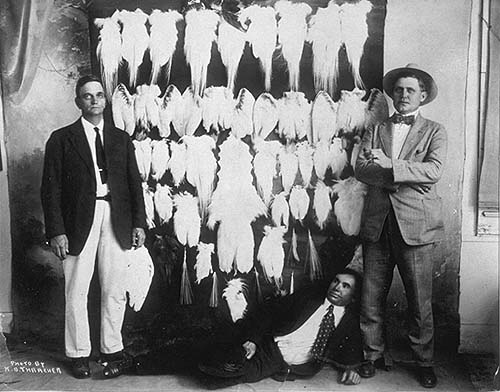

Even with mounting pressure from conservation lobbies, the plume industry stood fast against claims of cruelty and offered the public false assurances. For instance industry officials claimed that the bulk of feather collection was limited to shed plumes, however in truth, those ‘dead plumes’ brought only one fifth of the price of the live unblemished ones. To counteract the charges of cruelty, claims were circulated that most feather trim was either artificial or produced on foreign farms that exported molted feathers.

In reality throughout Australia, India and the Orinoco and Amazon Basins, the quantity of plumage gathered during the moult was minute and the majority of feathers arriving in London were virtually all from shot birds.

As long as the ‘harvesting’ of feathers was providing a lucrative income to plume hunters and feather merchants (the trade was worth some £2 million annually) they would continue their bloody slaughter:

|

PRICES OF RARE AND BEAUTIFUL BIRD SKINS IN LONDON |

||||

| Condor skins |

$3.50 |

to |

$5.75 |

|

| Condor wing feathers, each |

.05 |

|||

| Impeyan Pheasant |

.66 |

“ |

2.50 |

|

| Argus Pheasant |

3.60 |

“ |

3.85 |

|

| Tragopan Pheasant |

2.70 |

|||

| Silver Pheasant |

3.50 |

|||

| Golden Pheasant |

.34 |

“ |

.46 |

|

| Greater Bird of Paradise: | ||||

| Light Plumes: | Medium to giants |

10.32 |

“ |

21.00 |

| Medium to long, worn |

7.20 |

“ |

13.80 |

|

| Slight def. and plucked |

2.40 |

“ |

6.72 |

|

| Dark Plumes: | Medium to good long |

7.20 |

“ |

24.60 |

| 12-Wired Bird of Paradise |

1.44 |

“ |

1.80 |

|

| Rubra Bird of Paradise |

2.50 |

|||

| Rifle Bird of Paradise |

1.14 |

“ |

1.38 |

|

| King Bird of Paradise |

2.40 |

|||

| “Green” Bird of Paradise |

.38 |

“ |

.44 |

|

| East Indian Kingfisher |

.06 |

“ |

.07 |

|

| East Indian Parrots |

.03 |

|||

| Peacock Necks, gold and blue |

.24 |

“ |

.66 |

|

| Peacock Necks, blue and green |

.36 |

|||

| Scarlet Ibis |

.14 |

“ |

.24 |

|

| Toucan breasts |

.22 |

“ |

.26 |

|

| Red Tanagers |

.09 |

|||

| Orange Oriels |

.05 |

|||

| Indian Crows’ breasts |

.13 |

|||

| Indian Jays |

.04 |

|||

| Amethyst Hummingbirds |

.01½ |

|||

| Hummingbird, various |

3/16 of .01 |

“ |

.02 |

|

| Hummingbird, others |

1/32 of .01 |

“ |

.01 |

|

| Egret (“Osprey”) skins |

1.08 |

“ |

2.78 [Page 125] |

|

| Egret (“Osprey”) skins, long |

2.40 |

|||

| Vulture feathers, per pound |

.36 |

“ |

4.56 |

|

| Eagle, wing feathers, bundles of 100 |

.09 |

|||

| Hawk, wing feathers, bundles of 100 |

.12 |

|||

| Mandarin Ducks, per skin |

.15 |

|||

| Pheasant tail feathers, per pound |

1.80 |

|||

| Crown Pigeon heads, Victoria |

1.68 |

“ |

2.50 |

|

| Crown Pigeon heads, Coronatus |

.84 |

“ |

1.20 |

|

| Emu skins |

4.56 |

“ |

4.80 |

|

| Cassowary plumes, per ounce |

3.48 |

|||

| Swan skins |

.72 |

“ |

.74 |

|

| Kingfisher skins |

.07 |

“ |

.09 |

|

| African Golden Cuckoo |

1.68 |

|||

“Birds were trapped for the cage trade and limed, shot, bludgeoned or poisoned by the thousands of underemployed rural poor who provided raw materials for the milliner. Few species were spared the unwelcome attentions of the plumage hunters. Seabirds were especially in demand, and populations of gulls and kittiwakes were decimated to sustain the fashion for birds’ wings in women’s hats. As London and provincial dealers offered one shilling each for the wings of ‘white gulls’ in the 1860s, excursion trains left London for locations as far apart as Flamborough Head and the Isle of Wight carrying beer-swilling plumage hunters and their rook rifles towards the killing grounds. Some hunters abandoned any notion of ‘sport’ and contrived to catch gulls and kittiwakes on their nests. Subsequently, as one observer put it, ‘cutting their wings off and flinging the victim into the sea, to struggle with feet and head until death came slowly to their relief’”.”

Such was the demand for feather in Victorian times, that pressure was placed upon both domestic birds (Herons, Egrets, Great Crested Grebes) as well as those from the British colonies. Towards the end of the Victorian era in Britain, several waterfowl birds were seriously threatened with extinction due to the demands of feather fashions. For example, the skin and soft underpelt and head frills of the great crested grebe’s feathers (Podiceps cristatus ) were particularly in demand by the millinery trade to decorate ladies’ fancy hats and ruffs.

However early forms of legislation did nothing to halt the carnage and pillage for millinery purposes, of tropical and sub-tropical birds, to which the SPB was drawing attention regularly from the the 1890s onwards.

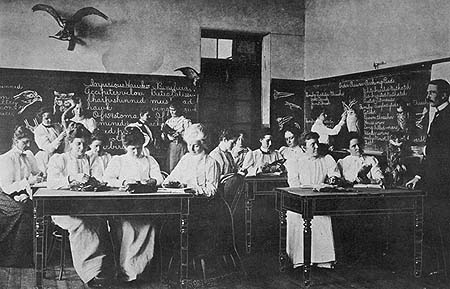

Founded in 1889 and chaired briefly by the naturalist and writer W. H. Hudson, the Society argued that the only feasible way to stop the slaughter of egrets, lyre birds, birds of Paradise and others was to destroy the plumage trade itself by persuading women to refuse to wear feathers.

Not surprisingly there was no shortage of men to line up and condemn female vanity. In a pamphlet titled “Feathered Women” the president of the SPB W. H. Hudson painted women as ‘bird-enemy’ and sought to persuade ladies to refrain from wearing feathered fashions by arguing they would never attract a mate:

“no man who has given any thought to the subject, who has any love of nature in his soul, can see a woman decorated with dead birds, or their wings, or nuptial plumes, without a feeling of repugnance for the wearer, however beautiful or charming she may be”.[5]

What Hudson’s campaigning failed to reflect was that in its earliest days RSPB membership consisted entirely of women who were moved by the emotional appeal of the plight of young birds left to starve in the nest after their parents had been shot for their plumes. The rules of the Society reflect its female membership and their active involvement in campaigning against the plumage trade:

- That Members shall discourage the wanton destruction of Birds, and interest themselves generally in their protection

- That Lady-Members shall refrain from wearing the feathers of any bird not killed for purposes of food, the ostrich only excepted.

Sandwich-men Employed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, that Patroled London Streets in July, 1911.

THE PLUMAGE BILL & VIRGINIA WOLF

Campaigns against ‘murderous millinery’ by the RSPB and others culminated in the 1920 Plumage Bill that was put to the parliamentary vote. On the 10th of July 1920 H. W. Massingham (1860-1924), writing under the nom de plume of ‘Wayfarer’, made the following comments concerning the failure of the 1920 Plumage Bill in the House of Commons:

“What does one expect? They have to be shot in parenthood for child-bearing women to flaunt the symbols of it, and, as Mr Hudson says, one bird shot for its plumage means ten other deadly wounds and the starvation of the young. But what do women care? Look at Regent Street this morning!”[6]

Virginia Woolf in her reply essay ‘The Plumage Bill’ responds to Massingham’s sexist charge with the creation of the character “Lady So-and-So”. Woolf proceeds to paint a harsh portrait of the unthinking, self indulgent woman of fashion – the buyer of a ‘lemon coloured egret’ – presenting her in a way that seems astonishingly to corroborate Massingham’s view. But in another twist, she renders a far more devastating portrait of men: the hunters and merchants that turn killing into a commodity, and the male parliament that fails to pass the plumage Bill prohibiting the trade. Woolf prompts her audience to question the social code that unconsciously condemns women’s pleasures – the love of beauty and fashion – as sin whereas men’s pleasures – their lusts for hunting, women, money – are accepted even valorised:

“Can it be that it is a graver sin to be unjust to women than to torture birds?”

However, while Lady So-and-So is a creation of a patriarchal system of male production and wealth and a patriarchal aristocracy, she is also a reflection/product of patriarchal society as produced and consumed by women. Lady So-and-So’s existence as a consumer, and a flawlessly finished consumer icon at that, was at least partly the work of women producers of luxury goods or services. For example the ‘lemon coloured egret’ was almost certainly dyed by female hands; in 1889, in London and Paris over 8000 women were employed in the millinery trade and the majority of the 83,000 people employed in New York City in 1900 in the making and decorating of hats were women.

A class-bound Woolf may have been ignorant of this point, or, more likely, intentionally ignored it so she could highlight the male producers and profiteers controlling the trade. Whatever her reasons, the lasting point she makes in her essay is that, with cash in hand, Lady So-and-So had every right to buy the beautiful complementary accessory for her opera ensemble, an accessory deemed by the fashion press to be worthy of Lady So-and-So and the occasion, as Wolf so cuttingly observes:

“Lady So-and-So was looking lovely with a lemon coloured egret in her hair”.

Sound familiar?

Kate Middleton has apparently employed famed milliner Phillip Treacy to make fascinators for the wedding party.

The Plumage Act entered the Statute Book a year later in 1921. A bill “to prohibit the sale, hire, or exchange of the plumage and skins of certain wild birds”, The Plumage Act was celebrated as the factor that brought an end to the “Age of Extermination”. How much this change was due to the effects of the Acts’ hunting and trade regulations or that a growing inclination toward promoting humanitarian ideals reduced the allure of feathered garb is not not clear. What is clear is that dwindling feather sales had as much do, if not more, with changes in the everyday lives of women which simply eliminated opportunities to wear oversized, constraining hats.

Frank Chapman’s 1886 Feathered Hat Census

|

BIRD SPECIES |

# HATS SEEN |

BIRD SPECIES |

# HATS SEEN |

| Grebes |

7 |

Blue Jay |

5 |

| Green-backed Heron |

1 |

Eastern Bluebird |

3 |

| Virginia Rail |

1 |

American Robin |

4 |

| Greater Yellowlegs |

1 |

Northern Shrike |

1 |

| Sanderling |

5 |

Brown Thrasher |

1 |

| Laughing Gull |

1 |

Bohemian Waxwing |

1 |

| Common Tern |

21 |

Cedar Waxwing |

23 |

| Black Tern |

1 |

Blackburnian Warbler |

1 |

| Ruffed Grouse |

2 |

Blackpoll Warbler |

3 |

| Greater Prairie Chicken |

1 |

Wilson’s Warbler |

3 |

| Northern Bobwhite |

16 |

Tree Sparrow |

2 |

| California Quail |

2 |

White-throated Sparrow |

1 |

| Mourning Dove |

1 |

Snow Bunting |

15 |

| Northern Saw-whet Owl |

1 |

Bobolink |

1 |

| Northern Flicker |

21 |

Meadowlarks |

2 |

| Red-headed Woodpecker |

2 |

Common Grackle |

5 |

| Pileated Woodpecker |

1 |

Northern Oriole |

9 |

| Eastern Kingbird |

1 |

Scarlet Tanager |

3 |

| Scissor-tailed Flycatcher |

1 |

Pine Grosbeak |

1 |

| Tree Swallow |

1 |

(Modified from Strom, 1986.)

In an attempt to conserve certain wild bird populations, the U.S. Congress enacted legislation beginning in 1900, restricting the harvest and possession of egret bird skins and feathers and employed federal agents to confiscate banned egret skins when intercepted.

If, for example, egrets protected from killing by Alabama law were shot and their feathers shipped across state lines to New York, a Lacey Act violation would have been committed. The Act ended most of the commercial plume trade in Native American birds. The failure of some states to enact laws to protect their wildlife kept the Act from being 100 percent effective. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 closed these loopholes by protecting all native migratory birds.

Yet, as absurd as it may sound, it was really a fashionable new hairstyle that ultimately saved the birds. In 1913, the bob and other short hairstyles were introduced—cuts which would not support large extravagant hats. Plain slouch hats and ‘cloches’ became very popular, and it was for this reason that most plume-hunters were forced to abandon their trade. Thus ended the “Age of Extermination” and the possession and displaying feathers became, once again, an avian trait.

Muderous Millinery by Dr Merle Patchett is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

[1] Hornaday, W. T (1913) Our Vanishing Wildlife: Its Extermination and Preservation. e-book available http://www.gutenburg.net.

[2] Moore-Colyer, R. J. (2000) ‘Feathered Women and Persecuted Birds; The Struggle Against the Plumage Trade c. 1860-1922’, Rural History, 11/1, pp. 57-73.

[3] Figures from Doughty, R. W. (1975) Feather Fashions and Bird Preservation: a Study in Nature Protection. University of California Press.

[4] Figures from Doughty, R. W. (1975) Feather Fashions and Bird Preservation: a Study in Nature Protection. University of California Press.

[5] Moore-Colyer, R. J. (2000) ‘Feathered Women and Persecuted Birds; The Struggle Against the Plumage Trade c. 1860-1922’, Rural History, 11/1, pp. 57-73.

[6] Abbott, R. (1995) ‘Birds Don’t Sing in Greek: Virginia Woolf and “The Plumage Bill”‘, in C. J. Adams and J. Donovan’s (eds) Animals and Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations. Duke University Press.

[7] Extract from a paper read at the World’s Congress on Ornithology, Chicago, 1897. Quoted in Doughty, R. W. (1975) Feather Fashions and Bird Preservation: a Study in Nature Protection. University of California Press.

you have put together a phenomenal blog/site . . well done – are you going to put it all together in a book one day? I came across your blog while putting together my own blog as I have just written a short article on the Racquet-tailed Drongo . . and – as an aside – believe that the tail feathers of this species adorned one of the hats worn by Audrey Hepburn in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ . . you can visit my blog and the drongo article here: http://duncanbutchart.wordpress.com/ . . . duncan butchart, nelspruit, south africa

If each living being that appears in our life is a symbol, a message, to guide us on our Path while living on Earth, what is the message with wearing a dead bird? The skins of the hummingbirds shown in your photo a reminder that the joy associated with the appearance of a hummingbird seen in nature can so easily be obtained by us all when we “Walk Gently on Mother Earth’s Back”.